Emerging Role of Project Management in the Drug Development Life Cycle and Supply Chain

Introducing “Project Manager” in Healthcare Environment

The global impact of COVID 19 pandemic surfaced questions about timelines for vaccine development, drug quality and efficacy, and risks associated with any side effects of the vaccines, etc. The pharmaceutical companies focus on developing the vaccines and getting them approved for patients. Simultaneously, they evaluate steps for developing and mass-producing the vaccines while ensuring that the drug will not lose its strength during storage and transport. The clinicians need informational updates on vaccine development, administration and storage. Everyone needs a combination of printed materials, multichannel notifications about the vaccine, and services on the adherence protocols to ensure people are safe.

No one can miss the fact that these discussions above require bringing multiple people together at various points. Brainstorming alternative thoughts and making decisions becomes pivotal to properly planning work proactively. That thought process of how one brings multiple together, communicates adequately and appropriately, and delivers on the important and minimum requirements. The role that interfaces strategically on the outcomes and benefits while also removing impediments for the delivery team to deliver promised outputs on time, on budget, and on scope is the “Project Manager”.

Demystifying Project Management

Frequently, questions arise on the role of project manager in healthcare projects. On the one side, management scientists question the value of project management in their preclinical or clinical work. Their questions revolve around the lack of scientific knowledge to manage drug development in healthcare initiatives. On the other side, the surge of lean and agile approaches to managing initiatives, such as Scrum or Kanban, do not recognize the project manager role emphasizing that project management is losing its foothold. While the larger community of professionals from management and science discuss the role of project management as a discipline in the healthcare domain, the patients, physicians, and providers are gravely concerned about their health, quality of care, and adherence protocols. So, let us review these areas more closely.

Clinical Setting

Each stage in drug development is full of uncertainties. Although clinical scientists design experiments in laboratories, they formulate hypotheses with a goal. As the hypotheses are proved or disproved, they continuously define and refine the experiments. Every experiment is loaded with cost, and the exit criteria is outlined indicating “when” to shift focus to a different mechanism of action or another new molecule development. This process requires scientists to work with many types of stakeholders as they communicate their findings through the governance framework and to ask for more funds towards the capital expense and operating expense to procure resources. So, even when clinical research scientists don’t recognize the need for project managers, they are taking on the responsibilities of project management in terms of delivering through people. Imagine if clinical scientists had project managers to navigate through this ambiguity. How much of their capacity will be relieved if they are not managing stakeholders, resolving conflicts, responding to risks, and upholding quality?

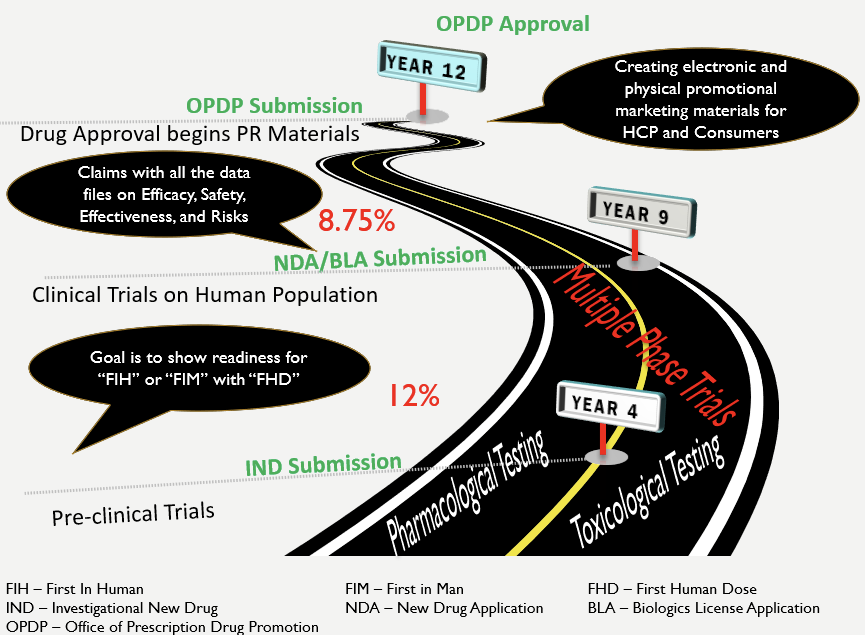

Previously, it took approx. 12 years to develop a drug and get it approved for the market (MedicineNet, 1999). We have reduced this timeframe, especially in the context of COVID-19. Yet, the astronomical costs of drug development (PhRMA, 2015) even before the onset of COVID-19 emphasize that various stakeholder groups need to be constantly engaged to address the many risks in drug development and drug distribution (Sullivan, 2019). None of these imperatives of controlling risks, ensuring quality, engaging stakeholders, and delivering on schedule can be fully upheld by the same people that are also involved in drug development. Nor should they be asked to. After all, none of us want to see Thalidomide experience again when quality is compromised for speed to market!

Drug Discovery Roadmap

Agile Context

Consider, for a moment, Agile approaches. One of the principles of Agile Manifesto emphasizes “customer collaboration”. But when it comes to healthcare, who is the customer? For example, a physician prescribes a drug to a patient. The drug is developed by a pharmaceutical company. The patient is the customer because the patient buys the pharmaceutical company’s drug through the resellers, i.e. pharmacies. The exchange of value – money exchanged for a product or service – is between a patient and a physician. The physician will be a client providing medical expertise to the pharmaceutical company. In this example, how is feedback collected by clinical research scientists in drug development? Certainly, anyone can develop and host a survey. But it requires a competent person working with multiple teams to orchestrate different approaches to collect patient input through multiple channels. This person will then track progress, and analyze data to come up with predictive and prescriptive insights. That role is the project manager and even if that titled role is missing, some members are picking up that responsibility to deliver.

Let us shift our attention to Scrum. Scrum can be viewed as a framework for delivering incremental business value in an environment of evolving requirements. It provides an opportunity to ask powerful questions frequently to provide customer satisfaction through early delivery of value. A pattern of “customer satisfaction” is already emerging here. Although Scrum does not treat project management as a role, it recognizes that every sprint can be treated like a mini project. When one looks closely at the rationale behind Scrum and its successes, one discovers that Scrum leverages the concept of fixing the time/duration to deliver an increment. The advantages are clear because such mini-project treatment with a 2-4-week window puts a boundary on the cost that can be incurred or the risks that can materialize. Consequently, we eliminate working longer hours by getting early feedback to take corrective and preventive actions (CAPA, that regulated industry emphasizes).

Yet another set of voices that emerges frequently proclaims: “But we can’t use Agile or Scrum in healthcare”. Some healthcare providers claim that Agile and Scrum are for software development. A few years back, a Clinical Research Scientist I had worked with reasoned, “Drug development is not the same as Software development.” However, drugs:

- are developed by experiments just like software is developed in iterations

- can address a specific problem like how a software addresses a specific challenge

- can’t work with everyone just like a software will not satisfy everyone’s need

- can have side effects and software can have similar disadvantages too

- can adversely impact people's lives and some software, esp., used for running diagnostic and surgical equipment can have fatal consequences too.

So, if Agile or Scrum can be used for software development, why can’t the same be used in healthcare settings? It is the mindset that requires change.

“Healthcare is different because the treatment options are different for everyone and because it follows a linear pattern,” mentioned my physiotherapist. I couldn’t agree more with one part of that statement. Even outside of drug development, patients’ conditions are treated based on the exploration of their symptoms, severity of their condition, history, pain tolerance, allergy profile, and other variables. And, how do doctors and therapists operationalize this information? They:

- make a plan based on things that can’t be ignored (risk)

- take a calculated approach to addressing the problem (scope) within a specific timeframe (schedule)

- check for the adverse effects of drugs and the efficacy of treatment (quality).

- have some cost involved and no one jumps to a surgical solution immediately.

So, even in a clinical and therapeutic setting, the project variables apply, and the iterative approaches are the norm! However, when we restrict ourselves to our own profession, such as clinical research, clinical care, hospital floors, and other diagnostic, therapeutic, and surgical care, we fail to see the benefits of other professions such as project management discipline, agility, and lean principles.

Pre-Clinical Considerations in Drug Development

Emerging Role of Project Management

Project Management has evolved to the extent where Project Managers are now seen as contributory board members in the executive suite. Deguire (2011) and Wagner (2017) called for a more formal “Chief Project Officer” role that will head the project delivery excellence and will balance the operational excellence with strategic benefits. A TONES framework highlights the various roles that critical middle management (i.e., project management) should play in the emerging world (Rajagopalan, 2016). A view of project management being concerned with tracking status updates and scheduling meetings (although that is not what project management ever was) has been in the rearview mirror for several years.

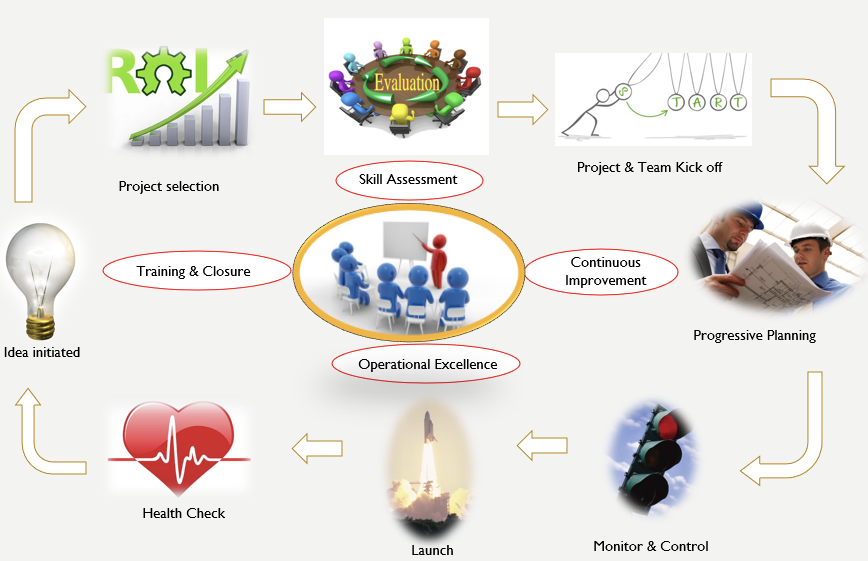

Consider the Project Management Institute’s latest guide of PMBOK v7. There, one can observe a clear shift from the process-driven approach to principle-driven approach. Instead of recognizing the five process groups, the latest edition of PMBOK recognizes 12 project delivery principles spread over eight domain areas. Consequently, project management in the healthcare domain has to be strategic about project selection, ongoing skill assessment for talent management, continuous improvement for transition and succession management, operational excellence for capacity and capability management, and training towards benefit delivery, transition, and sustenance.

Similarly, the Agile framework is celebrating its 20th anniversary and is now looking at expanding the applicability of agile beyond software development and into social life, education, youth leadership, etc. While Scrum doesn’t call out for a project manager role, Scrum emphasizes the product owner and scrum master roles where project management roles are distributed. As a result, the project managers have to step beyond the titles of technical aspects of project management and step into the increased responsibilities of strategic and business functions and demonstrate leadership beyond team management.

Emerging Focus of Project Management Role

Healthcare Delivery Management

It is widely believed that the outcomes-based strategic management is critical in the healthcare context. As a result, understanding the strategic focus permeates all project delivery frameworks in healthcare. In drug discovery, this outcomes-management is focused on a total cost of ownership by looking at the principles and processes that eliminate waste and increase value. Regardless of their formal titles, those in the hospitals and clinic administration can evaluate processes that address risk. This could involve:

- an independent review of pre-surgical check-in

- checking for enhanced vitals such as adverse reactions for medicines taken

- the impact of over-the-counter medicines and their interactions

- the use of Kanban boards for maintaining patient checks, and others.

The non-clinical drug development can look at processes to check for specific pathway analysis and documentation of results to better support the regulatory appeals processes. Post-approval development may involve GxP considerations. For instance, the general lab practices can be expanded to audit controls that ensure uniformity, reproducibility, and reliability whereas the general manufacturing practices can be reviewed for safety, stability, and sustainability. All these requirements will need careful workflow processes for regulatory compliance.

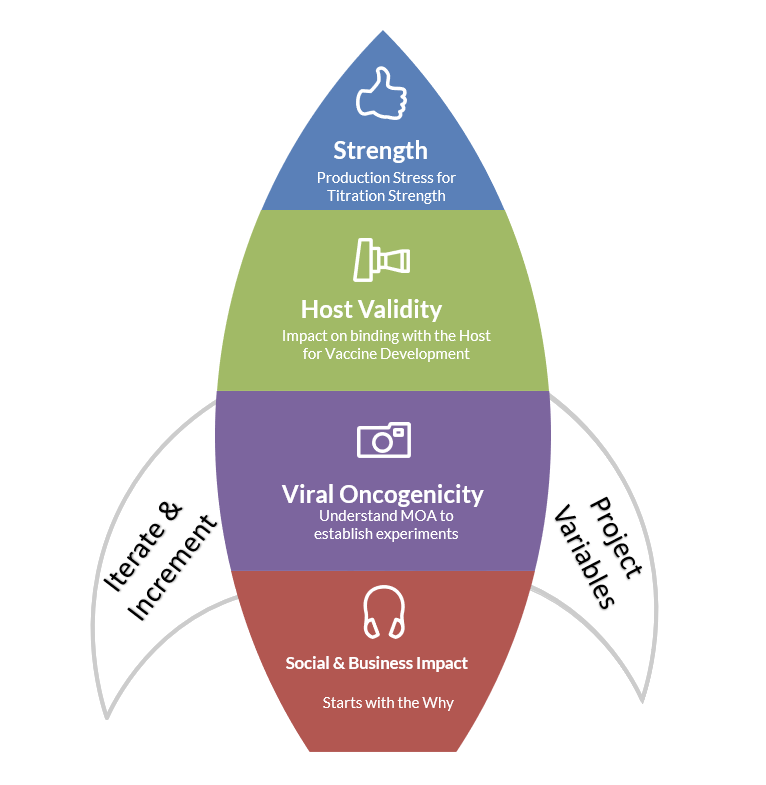

Instead of thinking of the pre-clinical, clinical, and post-clinical states as completely linear, iterative thinking can be applied where considerations for social and business impact, viral oncogenicity, host validity, and strength validation can be set up prior to drugs entering the clinical studies. Similarly, the branded and unbranded clinical messages for multiple channels and platforms for physicians and consumers can be thought through separately. These approaches can streamline delivery and expedite adoption, if and when they are supported by training materials to onboard early.

The healthcare project management can leverage sophisticated data analytics using robotics and machine learning and unearth hidden insights from data collected. These data insights can be further fed into the clinical and pre-clinical studies or enable the refinement of post-clinical marketing messages.

Conclusion

When it comes to managing projects in healthcare, the focus should shift from project delivery framework to caring for end-users’ health. Infusing the system with customer feedback is a good start but doesn’t automatically guarantee results. To effectively lead these healthcare initiatives, flexibility to unlearn the old ways of managing projects and learn new ways of working with principles is pivotal. All of the above applies to any type of healthcare projects, including but not limited to the healthcare information management, electronic medical records, drug development, drug promotion, supply chain management, etc.

References

Deguire, M. (2011). PMs in the boardroom! Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2011—EMEA, Dublin, Leinster, Ireland. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute. Retrieved Jan 17, 2021, from https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/boardroom-chief-project-officer-manager-6122

Medicine.net (n.d.). Drug Approvals – From Invention to the Market … 12-Year Trip. Retrieved May 11, 2020, from https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=9877

PhRMA (2015). Biopharmaceutical Research and Development. Retrieved May 11, 2020, from http://phrma-docs.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/rd_brochure_022307.pdf

Rajagopalan, S. (2016, July). TONES: A reference framework for identifying skills and competencies and grooming talent to transform middle management through the field of Project Management. International Journal of Markets and Business Systems, 2(1), 3-24.

Sullivan, T. (2019). A Tough Road: Cost to develop one drug is $2.6 Billion; approval rate for drugs entering clinical development is less than 12%. Retrieved May 11, 2020, from https://www.policymed.com/2014/12/a-tough-road-cost-to-develop-one-new-drug-is-26-billion-approval-rate-for-drugs-entering-clinical-de.html

Wagner, R. (2017). The Chief Project Officer (CPO) - A new role for project-oriented organizations. International Project Management Association. Retrieved Jan 23, 2021 from https://www.ipma.world/chief-project-officer-cpo-new-role-project-oriented-organisations/